|

Thoughts and Artifacts Relating to the Battle of the Little Bighorn |

by Ted Koelikamp, |

| Central States Archaeological Societies 2019

January Journal |

Crown Point, Indiana |

|

This is an excerpt from "Thoughts and

Artifacts Relating to the Battle of the Little Bighorn".

Read the complete column in the Central

States Archaeological Societies 2019

January Journal which can be purchased on-line after March 2020

|

|

|

|

|

In the last 150 years, much has been written

about the Battle of the Little Bighorn, otherwise known

as “Custer’s last Stand.” There have been many conflicting

reports, both by participants and historians on what

really happened and why the U.S. military lost. The end

result is known, with 268 U.S. Cavalryman killed, 59

wounded and 25 missing. On the American Indian side,

it is estimated that 150 warriors were lost, but that figure

is only conjecture.

Custer’s defeat was not the worst loss of the

U.S. military against the American Indians, but it is the

most remembered. Most notably, in 1791, under General

St. Clair, more than 1000 soldiers were killed along with

200 additional camp followers in a campaign against a

coalition of American Indian led by Little Turtle. This

engagement, known as the Battle of the Wabash, is considered

the worst defeat for the U.S. Army in the history

of the North American Indian wars.

It has been estimated that there were about

3000 warriors in the Little Bighorn battle compared to

nearly 600 soldiers. The real disparity, however, was

not so much in numbers as in the wide distribution of

troopers and in fire power. It is thought that nearly half

of the American Indian combatants had guns and about

half of those, nearly 750, had repeating arms such as

Sharps, Spencers, Henrys and Winchesters. The soldiers,

on the other hand, had the single shot breech loading

45/55 carbine (Model 1873), which had a limited

range. It was later reported that the soldiers had trouble

ejecting the carbine cartridges due to verdigris (green

corrosion) build up in the leather loops of their cartridge

belts and the resulting deposits on the brass cartridges.

They had to use pocket knives to pry out the cartridges

from the heated barrels. They also carried Model 1872

Colt single action Army issued six shot pistols, but these

were only good at close range. This was proven true as

archaeological investigations in the 1980s showed they

were only used during the closing moments of the battle

as evidenced by these being found mostly on and around

Custer Hill.

The American Indians, based on field research

(metal detecting) during the 1984-85 seasons, remained

in groups off at a distance and behind hills, pouring fire

down onto Custer’s group of 13 officers and 208 men until they were

quite decimated. Only after most of

Custer’s men were either dead or wounded did the

American Indians charge and overwhelm them.

Luckily, Major Reno and Captain Benteen

with 16 officers with 274 men between them, eventually

dug into a hill about 4 ½ miles to the east of Custer.

One attempt to reach Custer by a detachment of troopers

under the command of Captains Weir and Benteen

was driven back to their bluff position. Custer’s position

had already been overrun around that same time. Reno

and Benteen were able to hold off the warriors from this

bluff position until reinforcements arrived under the

command of General Terry from the west. Terry and his

men were the first to find the scattered nude and mutilated

bodies of Custer’s command. Only the trumpeter,

John Martini, survived because he was sent back to the

pack train to tell them to hurry with ammunition.

Read the complete column in the Central States Archaeological Societies 2019

January Journal which can be purchased on-line after March 2020

|

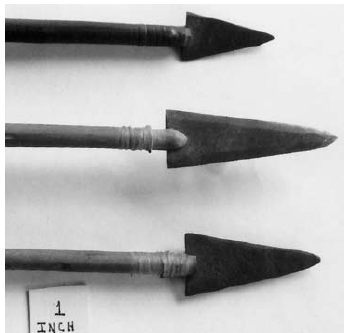

| The representative arrows shown in Figure 2,

have metal points which are typical of those used in the

battle. These cut metal points were either made by the

American Indians or obtained from traders. The points

were tied to the shaft with sinew and each arrow had

identifying marks and the colors of the owner. |

| |

| Read the complete column in the Central States Archaeological

Societies 2019 January Journal which

can be purchased on-line after March 2020 |

|

|